Cities are strange creatures. They are neither fully designed, nor fully self-organised. Their spatial production is partly controlled by central forces of urban planning, architecture, and technology, and partly by decentralised social, economic, political and technological processes enacted by millions of inhabitants. So, one is tempted to say, they are part complex engineered products, part biological organism.

The two important scientific questions lying at opposite ends of the spectrum are: (a) what makes a city similar to all other cities in the world, and (b) what gives a city its own unique identity? The first question is the search for universal laws. The second one, the search for explanations of diversity and heterogeneity. One could agree that the New York and Mumbai metropolitan regions, both roughly having populations around the 20 million mark, are definitive economic hubs for their nations, respectively. But, to what extent could we claim similarity, and to what extent difference? Both questions would need to be answered, before we can formulate and solve for the laws of cities.

Recent research from the Santa Fe Institute has started to provide insight into the first question. This paper has shown that many diverse properties of cities, from economic productivity and innovation potential, to lengths of infrastructure networks, follow universal scaling laws when measured against city population size. Put simply, the population of a city is a good indicator for several of its behaviours. It was found that all material resources (such as infrastructure and road networks) showed economies of scale and scaled sub-linearly with population size. On the other hand, most social and economic indicators (such as incomes, wealth, patents, crime) showed increasing returns and scaled super-linearly with population size. This leads to the postulated theory behind the existence of cities: urban agglomerations exist because it is inherently advantageous for them to exist. As population grows, the per capita expenditure on maintaining the urban system is less than the per capita socio-economic returns by way of income generation and wealth (although negative aspects such as crime grow super-linearly too).

These findings imply that larger cities are somehow more advantageous, since the larger the size of the urban system, the larger the production of wealth and innovation, and smaller the investment to sustain the system. However, what is also well known is that total wealth and income and the distribution of this wealth and income are two totally separate things. Bigger cities are certainly more wealthy, but do they make all inhabitants proportionately more wealthy too?

At the Sydney Urban Lab we studied scaling of per capita incomes for separate census defined income categories against population size for the whole of Australia. Read our paper here.

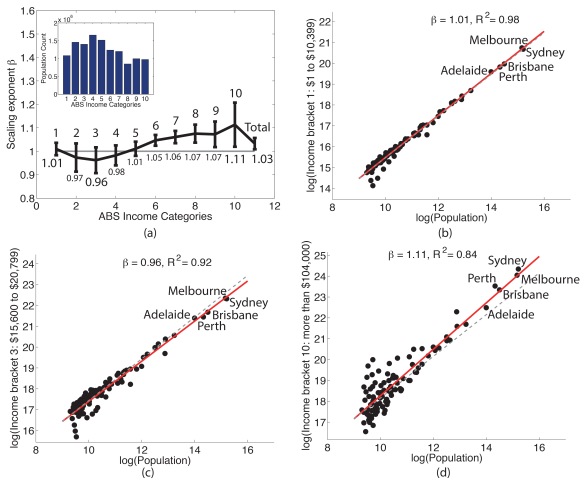

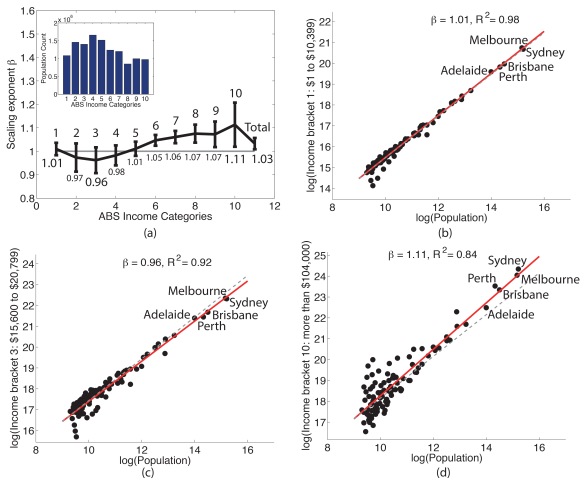

Across several urban area definitions, we find that lowest incomes grow just linearly or sub-linearly, whereas highest incomes grow super-linearly, with total income just super-linear. These findings support the earlier Santa Fe finding: the bigger the city, the richer the city, though the (just) super-linear scaling of total income was more consistent with the findings here. But, most importantly, we see an emergent metric of inequality: the larger the population size and densities of a city, higher incomes grow more quickly than lower, suggesting a disproportionate agglomeration of incomes in the highest income categories in big cities. Put simply, if you had low income, you are as likely to be found in a small city as in a big city. But, your costs of living in a bigger city would be higher, making you relatively poorer in a bigger city for the same income. But, if you had the highest incomes, you would be much more likely to be found in a much larger city. For you also the costs of living would certainly be higher, but it remains for future research to uncover the relative advantage you can gain by being able to afford better things in a bigger city on a higher income, e.g. education and private health services, and how this compares with the relative ratios of what can be afforded on lower incomes. Future research will also need to uncover the relationships of these findings to the indices of inequality measurement.

Because there are many more people on lower incomes that scale sub-linearly as compared to the highest that scale super-linearly, these findings suggest a scaling of inequality: the larger the population, the greater the inequality. Urban and economic planning will need to examine ways in which larger cities can be made more equitable.

Figure 1. Scaling of income in all 101 Significant Urban Areas (SUAs) in Australia. (a) Scaling exponents with 95% CI in 10 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) income categories. (b-d) Scaling behaviour for income categories 1, 3, and 10, (roughly categorised as lowest, middle lower, and highest, respectively), showing linear to sub-linear behaviours in the lower income categories, with super-linear behaviour emerging for higher income categories.

Figure 2. Scaling of income in high population density SUAs. (a) Log-log plot of population count versus population density for all 101 SUAs shows the general positive correlation of higher population with higher density. Sizes of circles scaled corresponding to total population counts. (b) Plot of population count against population density shows some outliers. E.g. High population, lower densities, or low populations with higher densities. The cut-off point for excluding all SUAs where both population counts as well as population densities are low occurs at around 152 persons per sq km. (Bathurst). (c) Scaling exponents with 95% CI in 10 ABS income categories for the top 66 highest density and population count SUAs. (d-g) Scaling behaviour for income categories 1, 3, 4, and 10, (roughly categorised as lowest, middle lower, and highest, respectively), showing linear to sub-linear behaviours in the lower income categories, with super-linear behaviour emerging for higher income categories for the 66 high population and high density SUAs.

Figure 3. Scaling of income in SUAs by population count cut-offs. Scaling exponents with 95% CI in 10 ABS income categories for SUAs over (a) 30 000 total population, (b) 40 000 population, and (c) 80 000 population, showing linear to sub-linear behaviours in the lower income categories, with super-linear behaviour emerging for higher income categories.